Even for space systems, TCP/IP is oftentimes an important component in some shape or form because the majority of development might still occur on ground where an internet connection is still available. The special thing about space is that instead of using newline and/or UTF-8 based data, the data is generally in binary format and packet based. The most prevalent of the space packet standards is probably the CCSDS Space Packet Protocol.

TCP is always a tricky protocol when exchanging something like CCSDS space packets. UDP is

generally a better fit because a packet can simply be exchanged as a datagram. However, there

are special cases where TCP is simply more convenient, for example when using something like

SSH tunneling, which would require some socat trickery to use UDP. Sometimes, we would also like

to have the additional guarantees that TCP has in comparison to UDP.

What I already have

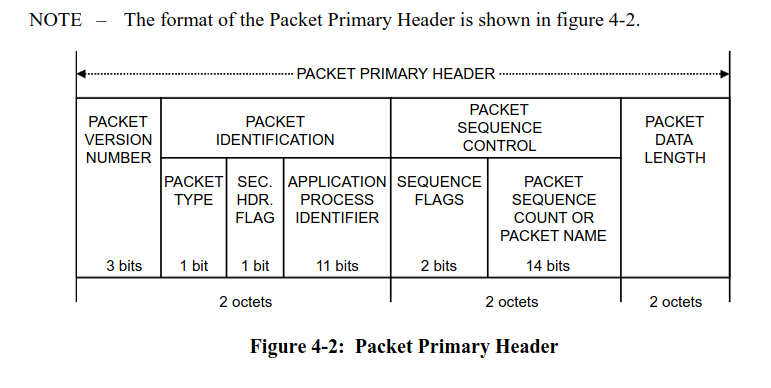

I already implemented a TCP server implementation for C++ which is able to exchange tightly packed CCSDS space packets. The only thing all CCSDS space packets have in common is a six byte header, shown in the following image:

CCSDS space packet header

The Packet Identification field (Packet ID) can be used specifically as a start marker to detect packets from a raw bytestream. After detecting the start of a packet, the fifth and sixth byte can be used to know the size of the full packet. This still is not a perfect transport layer in my opinion, because it is still missing proper framing. However, with the assumption that TCP guarantees full data integrity and some robust CCSDS parsing, I am generally happy with this, as it allows to simply send and read possibly multiple CCSDS space packets in one go without any additional framing protocols on top.

Moving to Rust

I recently implemented a TCP server for the sat-rs

Rust framework with the goal to have a similar behaviour as the C++ variant. Additionally, I also

had to goal to allow more than just CCSDS space packets by using the COBS

protocol as a generic framing mechanism. This would in theory also allow to exchange something

like USLP frames.

After implementing this second variant first, I quickly noticed that the first variant using COBS encoded packets would share a lot of common code with the first variant exchanging CCSDS space packets only. This is because the process of reading a bytestream and extracting frames from that bytestream using a certain parsing protocol is common for both variants. The same is also true for the telemetry sent back to a client: It might be necessary to apply some encoding logic on the raw packets before sending them, but other than that, the logic is the same.

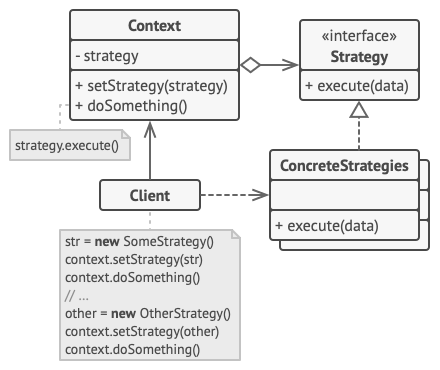

The Strategy Pattern

Coming from languages and projects which use object orientation heavily, my first thought was to use the template method pattern here. However, Rust does not allow inheritance, so I quickly determined that the strategy pattern would be the best fit here. If you do not know what the strategy pattern is, I recommend reading the article by Refactoring Guru. The following graph, which is taken from the article as well 1, shows the basic idea:

The Strategy Design Pattern

The strategy pattern allows to have a base algorithm with flexible adaption points which are called strategies. This pattern can be mapped on our problem and to Rust: The context object will be our generic TCP server which has some common logic to read TCs from a client and send back telemetry to the client. The Strategy interface is some trait which supplies all information required to parse telecommands from a raw bytestream or send telemetry back to the client. A concrete implementation would then for example be a COBS decoder object.

The generic TCP server

The basic tasks of the generic TCP server object are the following:

- Listen for TCP connections.

- If a client connects, accept the connection. Start reading the bytestream sent from the client until it is exhausted, or the used TC buffer is full. Exhausted means that the client stop sending telecommands (receiver timeout) or shuts down the writer side.

- If something was read from the client, start parsing for frames. This is where the strategy pattern comes in: I’d like the parsing algorithm to be something which can be different depending on which TC parsing strategy I am using, or more specifically, the strategy which I configured for that class.

- After a reader timeout or having read all packets, I also want to send back telemetry to the client. Here, I might have to apply custom protocols to the packets I want to send as well, so I want to apply an encoding algorithm depending on which TM strategy is used.

After a bit of cleaning up, this is what the general structure of the primary connection handler looked like, using some pseudo code as well:

pub fn handle_next_connection(

&mut self,

) -> Result<ConnectionResult, TcpTmtcError<TmError, TcError>> {

// This contains some context data about the handled connection, e.g. amount of handled TC

// and TM packets

let mut connection_result = ConnectionResult::default();

let mut current_write_idx;

let mut next_write_idx = 0;

let (mut stream, addr) = self.tcp_listener.accept()?;

stream.set_nonblocking(true)?;

connection_result.addr = Some(addr);

current_write_idx = next_write_idx;

loop {

let read_result = stream.read(&mut self.tc_buffer[current_write_idx..]);

match read_result {

Ok(0) => {

// Connection closed by client. If any TC was read, parse for complete packets.

// After that, break the outer loop.

if current_write_idx > 0 {

self.tc_handler.handle_tc_parsing(...)

}

break;

}

Ok(read_len) => {

current_write_idx += read_len;

// TC buffer is full, we must parse for complete packets now.

if current_write_idx == self.tc_buffer.capacity() {

self.tc_handler.handle_tc_parsing(...)

current_write_idx = next_write_idx;

}

}

Err(e) => match e.kind() {

// As per [TcpStream::set_read_timeout] documentation, this should work for

// both UNIX and Windows.

std::io::ErrorKind::WouldBlock | std::io::ErrorKind::TimedOut => {

self.tc_handler.handle_tc_parsing(...)

current_write_idx = next_write_idx;

if !self.tm_handler.handle_tm_sending(...)? {

// No TC read, no TM was sent, but the client has not disconnected.

// Perform an inner delay to avoid burning CPU time.

thread::sleep(self.base.inner_loop_delay);

}

}

_ => {

return Err(TcpTmtcError::Io(e));

}

},

}

}

self.tm_handler.handle_tm_sending(...)?;

Ok(connection_result)

}

The Strategy Interface and Implementation

In languages like C++ or Java, the strategy is generally an abstract interface specification

which is then implemented in form of concrete strategy objects. These concrete objects are then

passed to the context object which expects a concrete strategy as the adaption point for users.

In Rust, we can do these in a similar way: We specify an interface as a trait which provides

all information necessary to perform the parsing of telecommands or the encoding of telemetry.

In the example above, the tc_parser and tm_handler objects are either trait objects member or

generic members of the generic TCP server which implement the corresponding strategy traits.

After determining the necessary information for implementing the strategy, I have the following traits:

/// Generic parser abstraction for an object which can parse for telecommands given a raw

/// bytestream received from a TCP socket and send them to a generic [ReceivesTc] telecommand

/// receiver. This allows different encoding schemes for telecommands.

pub trait TcpTcParser<TmError, TcError> {

fn handle_tc_parsing(

&mut self,

tc_buffer: &mut [u8],

tc_receiver: &mut (impl ReceivesTc<Error = TcError> + ?Sized),

conn_result: &mut ConnectionResult,

current_write_idx: usize,

next_write_idx: &mut usize,

) -> Result<(), TcpTmtcError<TmError, TcError>>;

}

/// Generic sender abstraction for an object which can pull telemetry from a given TM source

/// using a [TmPacketSource] and then send them back to a client using a given [TcpStream].

/// The concrete implementation can also perform any encoding steps which are necessary before

/// sending back the data to a client.

pub trait TcpTmSender<TmError, TcError> {

fn handle_tm_sending(

&mut self,

tm_buffer: &mut [u8],

tm_source: &mut (impl TmPacketSource<Error = TmError> + ?Sized),

conn_result: &mut ConnectionResult,

stream: &mut TcpStream,

) -> Result<bool, TcpTmtcError<TmError, TcError>>;

}

Also note that we use another set of traits to allow passing found TC packets to a user using

a generic ReceivesTcCore base

trait. We also use a TmPacketSourceCore base trait as the generic trait for

user supplied telemetry packets. These also fit into the strategy pattern by allowing the user

to modify TC forwarding and TM specification through a generic contract.

We can now use generics to specify the strategy for the generic object. The generic TCP server class then looks like this:

pub struct TcpTmtcGenericServer<

TmError,

TcError,

TmSource: TmPacketSource<Error = TmError>,

TcReceiver: ReceivesTc<Error = TcError>,

TmSender: TcpTmSender<TmError, TcError>,

TcParser: TcpTcParser<TmError, TcError>,

> {

pub(crate) listener: TcpListener,

pub(crate) inner_loop_delay: Duration,

pub(crate) tm_source: TmSource,

pub(crate) tm_buffer: Vec<u8>,

pub(crate) tc_receiver: TcReceiver,

pub(crate) tc_buffer: Vec<u8>,

tc_handler: TcParser,

tm_handler: TmSender,

}

This is the concrete strategy implementation for COBS TC parsing:

/// Concrete [TcpTcParser] implementation for the [TcpTmtcInCobsServer].

#[derive(Default)]

pub struct CobsTcParser {}

impl<TmError, TcError: 'static> TcpTcParser<TmError, TcError> for CobsTcParser {

fn handle_tc_parsing(

&mut self,

tc_buffer: &mut [u8],

tc_receiver: &mut (impl ReceivesTc<Error = TcError> + ?Sized),

conn_result: &mut ConnectionResult,

current_write_idx: usize,

next_write_idx: &mut usize,

) -> Result<(), TcpTmtcError<TmError, TcError>> {

conn_result.num_received_tcs += parse_buffer_for_cobs_encoded_packets(

&mut tc_buffer[..current_write_idx],

tc_receiver.upcast_mut(),

next_write_idx,

)

.map_err(|e| TcpTmtcError::TcError(e))?;

Ok(())

}

}

where the concrete parser implementation can be found here. This the the implementation for COBS TM sending:

/// Concrete [TcpTmSender] implementation for the [TcpTmtcInCobsServer].

pub struct CobsTmSender {

tm_encoding_buffer: Vec<u8>,

}

impl CobsTmSender {

fn new(tm_buffer_size: usize) -> Self {

Self {

// The buffer should be large enough to hold the maximum expected TM size encoded with

// COBS.

tm_encoding_buffer: vec![0; cobs::max_encoding_length(tm_buffer_size)],

}

}

}

impl<TmError, TcError> TcpTmSender<TmError, TcError> for CobsTmSender {

fn handle_tm_sending(

&mut self,

tm_buffer: &mut [u8],

tm_source: &mut (impl TmPacketSource<Error = TmError> + ?Sized),

conn_result: &mut ConnectionResult,

stream: &mut TcpStream,

) -> Result<bool, TcpTmtcError<TmError, TcError>> {

let mut tm_was_sent = false;

loop {

// Write TM until TM source is exhausted. For now, there is no limit for the amount

// of TM written this way.

let read_tm_len = tm_source

.retrieve_packet(tm_buffer)

.map_err(|e| TcpTmtcError::TmError(e))?;

if read_tm_len == 0 {

return Ok(tm_was_sent);

}

tm_was_sent = true;

conn_result.num_sent_tms += 1;

// Encode into COBS and sent to client.

let mut current_idx = 0;

self.tm_encoding_buffer[current_idx] = 0;

current_idx += 1;

current_idx += encode(

&tm_buffer[..read_tm_len],

&mut self.tm_encoding_buffer[current_idx..],

);

self.tm_encoding_buffer[current_idx] = 0;

current_idx += 1;

stream.write_all(&self.tm_encoding_buffer[..current_idx])?;

}

}

}

In addition to the encoding which removes 0 from the packet, we also wrap telemetry packets with the sentinel byte 0.

Finally, we provide a concrete TcpTmtcInCobsServer class as a convenient object to instantiate

a TCP server with the TC strategy set to the CobsTcParser and the TM strategy set to the

CobsTmSender:

pub struct TcpTmtcInCobsServer<

TmError,

TcError: 'static,

TmSource: TmPacketSource<Error = TmError>,

TcReceiver: ReceivesTc<Error = TcError>,

> {

generic_server:

TcpTmtcGenericServer<TmError, TcError, TmSource, TcReceiver, CobsTmSender, CobsTcParser>,

}

impl<

TmError: 'static,

TcError: 'static,

TmSource: TmPacketSource<Error = TmError>,

TcReceiver: ReceivesTc<Error = TcError>,

> TcpTmtcInCobsServer<TmError, TcError, TmSource, TcReceiver>

{

/// Create a new TCP TMTC server which exchanges TMTC packets encoded with

/// [COBS protocol](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Consistent_Overhead_Byte_Stuffing).

///

/// ## Parameter

///

/// * `cfg` - Configuration of the server.

/// * `tm_source` - Generic TM source used by the server to pull telemetry packets which are

/// then sent back to the client.

/// * `tc_receiver` - Any received telecommands which were decoded successfully will be

/// forwarded to this TC receiver.

pub fn new(

cfg: ServerConfig,

tm_source: TmSource,

tc_receiver: TcReceiver,

) -> Result<Self, TcpTmtcError<TmError, TcError>> {

Ok(Self {

generic_server: TcpTmtcGenericServer::new(

cfg,

CobsTcParser::default(),

CobsTmSender::new(cfg.tm_buffer_size),

tm_source,

tc_receiver,

)?,

})

}

delegate! {

to self.generic_server {

pub fn listener(&mut self) -> &mut TcpListener;

/// Can be used to retrieve the local assigned address of the TCP server. This is especially

/// useful if using the port number 0 for OS auto-assignment.

pub fn local_addr(&self) -> std::io::Result<SocketAddr>;

/// Delegation to the [TcpTmtcGenericServer::handle_next_connection] call.

pub fn handle_next_connection(

&mut self,

) -> Result<ConnectionResult, TcpTmtcError<TmError, TcError>>;

}

}

}

I use the delegate crate to forwards all calls for the

public API to the internal generic TCP server. You can find the source code for the implementation

which can be used exchange CCSDS space packets

here.

Converting the code to use the strategy pattern definitely can be a challenge, but the good thing is that the core logic does not need to be changed or copy-and-pasted anymore when new encoding and decoding protocols for the data are required. The only thing that needs to be done is to create an own implementation of the strategy traits, and configure them via generics. In general, the strategy pattern is especially useful if you know that your class will have some common base logic with a few adaption point that should be user-configurable.

Conclusion

I think transferring object oriented design patterns to Rust can be tricky when coming from object oriented languages like Java, C++ or Python, because Rust does has not classic inheritance. It is still possible to apply most design patterns in Rust as well, using composition, generics and trait, but I oftentimes have the issue that a lot of the examples and resources available are contrived or only applicable for very simple problems. This post showed how to apply the strategy pattern in Rust for a TCP server to reduce duplicate code and allow flexbily adding new ways to parse packets received for that server, and to send telemetry.